These are unprecedented times, but the Football League also had to face the prospect of postponing or cancelling the season when war was declared on 4 August 1914. The league’s management committee met a few days later and concluded that it was business as usual, with one caveat: a number of grounds would be used for mobilisation purposes. White Hart Lane was requisitioned as a site for manufacturing protection equipment, such as gas masks, so Tottenham had to play their home matches at Highbury.

Many people believed the war would not last for longer than a few months. So, on 1 September, the Division One season kicked off with two fixtures. Manchester City beat Bradford City 4-1 in front of 9,000 fans at their Hyde Road ground while a crowd of 12,000 saw The Wednesday (they did not become Sheffield Wednesday until 1929) overcome Middlesbrough 3-1 at Hillsborough. On the same day, there were Division Two games at Arsenal, Clapton Orient and Grimsby.

Extraordinary as it may seem now, the season continued without any interruption until both divisions concluded in April 1915. The FA Cup also went ahead, with the final being played at Old Trafford rather than Crystal Palace as transport in London was proving difficult. Sheffield United beat Chelsea 3-0 on 24 April 1915, two days after the second battle of Ypres had begun. The justification for continuing the season was principally one of morale, in that it gave the public something to focus upon other than the limited and generally dire news filtering back from the front.

The importance of having football as some sort of safety valve that gave the country a chance to escape briefly from its worries does hold credence. Sports psychologist Michael Caulfield says sport, especially football, can provide joy and escapism in times of crisis. “Sport is a force and power for good,” says Caulfield. “It is the glue of society that binds schools, villages, cities, nations even. It matters more than we think and we should not belittle its impact.”

Plenty of people were opposed to the idea that fit, able-bodied men were continuing to play football while their peers were fighting in the trenches across the Channel. The RFU called off all rugby union games when the war was declared and the county cricket season was cancelled in September 1914, with Surrey declared champions based on the points they had accrued so far in the campaign.

The great England cricketer WG Grace could not fathom how football could continue during a period of national crisis and he voiced his concerns publicly through newspapers. The groundswell of negative opinion led to the issue being raised in parliament and the withdrawal of King George V’s patronage of the Football Association was even mooted.

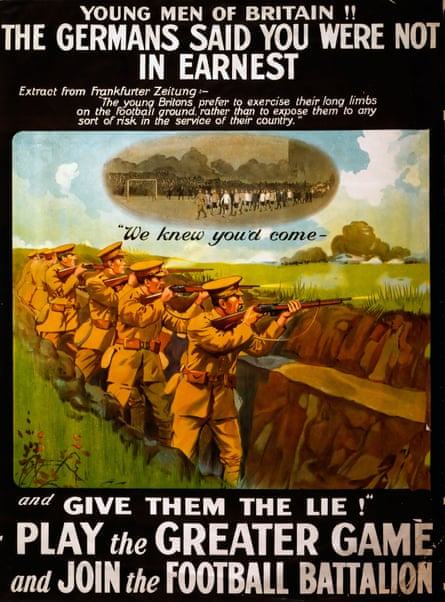

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also opposed the Football League’s decision to continue, arguing that players should have been joining the war effort. “If a footballer has strength of limb, let them march and serve in battle,” he declared. To head off the mounting criticism, the FA met with the War Office and these discussions led to the establishment of the Footballers’ Battalion in December 1914. The infantry battalion was part of the Middlesex Regiment and was mainly made up of professional footballers. Thirty joined at the outset and there were 122 onboard by March 1915. To compensate for the loss of personnel, clubs were allowed to pick guest players and some were even permitted to represent more than one club.

Walter Tull was among the players who joined the battalion. After excelling for Clapton, where he won the FA Amateur Cup, he moved to Tottenham and then to Northampton Town, where he had been managed by Herbert Chapman. Tull was one of Britain’s first black professional footballers and he became the army’s first black officer. He served in the Battle of the Somme and was cited for his “gallantry and coolness” when leading his company 0f 26 men to safety during operations in Italy. Tull was killed in action in March 1918.

The creation of the Footballers’ Battalion was a very effective way of swaying public opinion back in the favour of the sport. Colonel Henry Fenwick, the commanding officer in charge of the players, was impressed by their endeavour. “I knew nothing of professional footballers when I took over this, but I have learned to value them,” he said. “I would go anywhere with such men. Their esprit de corps was amazing. This feeling was mainly due to football - the link of fellowship which bound them together. Football has a wonderful grip on these men and the army generally.”

Buoyed by a more supportive atmosphere, the season was played out in its entirety, with the top divisions completing their 760 matches. However, the Football League was acutely aware that public opinion was turning, transport was becoming increasingly complicated, and more players were joining the armed forces or doing munitions work. They had little choice but to suspend league football and announced on 3 July 1915 that “a competition providing for promotion and relegation would be grossly unjust, would produce the greatest hardship to those who have made the greatest sacrifice, and would favour the club whose players have failed to realise their higher duty to the nation.”

Everton finished the 1914-15 season as champions, just one point above Oldham Athletic, but the real story was at the other end of the table. Chelsea and Tottenham finished 19th and 20th, respectively, and were due to be relegated. However, Manchester United had finished just one point above Chelsea and attention turned to their 2-0 win over Liverpool on Good Friday 1915.

Suspicions were raised by the referee about some of the Liverpool players’ lackadaisical approach. The Manchester Football Chronicle reporter was “surprised and disgusted” by the manner of United’s victory, with another reporter declaring the match as being “too poor to describe”. There were rumours that a group of players from both sides had met in a pub in Manchester beforehand to discuss the outcome, with bets placed at 8/1.

The Football League investigated and their findings were clear. Players from both teams had indeed placed substantial sums on the result. It was the first betting coup of its kind in English football and the punishments were suitably severe, with seven players – three United and four Liverpool – given lifetime bans.

When peace was declared in November 1918, the Football League agreed to restart with a new season in August 1919. But it was not immediately obvious which clubs should be relegated and which should be promoted. Manchester United could easily have gone down given that their players had fixed a match, but the club argued that they were unaware of the players’ betting arrangements and were allowed to keep the points they won against Liverpool. That left Chelsea and, to a lesser extent, Tottenham facing a very harsh relegation to Division Two.

In February 1919, the Football League reached a compromise. The First Division was expanded from 20 to 22 clubs and Chelsea were allowed to retain their status. It was agreed that the top two from Division Two – Derby and Preston – should join them but that still left one place available. Even though they had finished bottom of the league, Tottenham felt they had a good claim. As did Barnsley and Wolves, the clubs who finished third and fourth in Division Two.

The outlier in this were Arsenal, who had finished fifth in Division Two in the 1914-15 season and on the surface did not seem to have any right to be considered. However, Arsenal chairman Sir Henry Norris wielded considerable power. He had moved the club from Woolwich to Highbury in 1913, which left them in debt to the tune of £60,000 (£30m in today’s money), and was desperate to get them back into the top division. Norris, a property developer and MP, cajoled the Football League with an argument partly based on Arsenal being one of the oldest League clubs, partly through his force of personality and sphere of influence, and most persuasively of all, as Simon Inglis describes in his book, League Football and The Men who Made It, “by offering handsome inducements to other clubs or individuals.”

In the end, Wolves received four votes, Barnsley five, Tottenham eight and Arsenal 18. Norris had his way and Arsenal became the first club to be promoted to the top division of English football not on merit. They have not been relegated since so now hold the record for the longest continuous run in the top flight. It still rankles with many, no more so than a neighbouring club who were forced to play their matches at Arsenal’s ground in 1914-15, only to be ultimately displaced by them five years later.

Richard Foster’s new book Premier League Nuggets is out now and you can follow him on Twitter.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion